The Alchemy of Abstraction

On Georgia O'Keeffe, artistic (re)invention, and the abstracted art of looking.

Hello, my stars.

One quick housekeeping item before we dive in. Superstars, I will see you on Sunday at 11 am ET for our Monsters! hangout (Zoom link in this post). If you want to join us for this hour of creative discussion and inspiration, consider upgrading to a paid subscription! It’s less than $10 a month and keeps this newsletter humming along by keeping me fed and caffeinated.

Okay, onwards!

This week, we are going to discuss the Mother of American Modernism herself, Georgia O’Keeffe. You might know her as the lady who painted flowers that look like vaginas. However, that is just a tiny sliver of her work.

Born to Wisconsin dairy farmers in 1887, O’Keeffe created a mind-boggling range of work throughout her life - from totally abstract compositions to loose watercolor nudes to towering NYC cityscapes to bleached desert bones hovering over mountain ranges. She asserted that the sensuality in her paintings was not rooted in their similarities to genitalia, but rather in the innate sensuality of slow-looking and the natural forms in our world. Still, her identity as a woman played a significant role in how the art world perceived her, especially after she married photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz, her sometimes muse, sometimes abuser. O’Keeffe carefully crafted her mysterious image, prioritizing solitude and art-making until her death at age 98 in 1986.

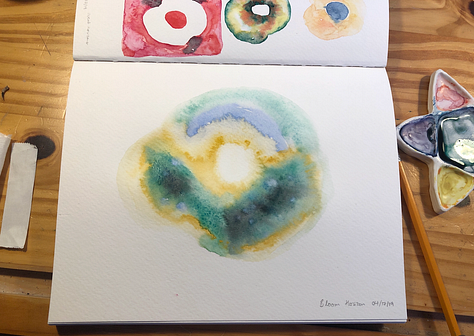

For a long time, I was only aware of O’Keeffe’s flowers and bones. When my friend Erin gifted me a slender catalog of the Canyon Suite paintings, it sent me tumbling down the rabbit hole of O’Keeffe’s abstract works and works on paper. Although the Canyon Suite series was later determined to not have been made by O’Keeffe (it’s unclear whether the works were deliberately faked or simply misattributed, more on that fiasco here), there are plenty of real examples of her watercolor works from this period. I could look at these loose, yet precise paintings for a long, long time. The richly saturated hues, the white slivers of negative space, the capillary action of the paint as it moves through the paper…so much to see and appreciate.

In 2018, the Whitney curated an exhibition titled “Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction” which chronicled the many shifts and evolutions in O’Keeffe’s style. Some pieces were based on actual organic forms and objects (plants, landscapes, and the sky, most often), others were inventions from her imagination with less clear origins. I was particularly drawn to the cresting waveform of Series I (pictured below), which would later inspire the background of my Three of Cups painting.

The forward to the exhibition text states:

Abstraction and representation for O’Keeffe were neither binary nor oppositional. She moved freely from one to the other, always cognizant that all art is rooted in an underlying abstract formal invention…As she said in 1976, “The abstraction is often the most definite form for the intangible thing in myself that I can only clarify in paint.” In other words, the definite and indefinite were intertwined in O’Keeffe’s art.

Even when O’Keeffe began to lose her eyesight (every artist’s nightmare), she pushed onwards her work turning briefly to sculpture, before finding her way back to the canvas with the help of studio assistants. These late paintings are dreamlike abstractions drawn from O’Keeffe’s imagination, a form of vision that not even blindness could take from her.

Last weekend, I attended a performance of The Alchemist’s Veil at La Mama Experimental Theater Company. In this work, Guggenheim dance artist Maureen Fleming creates a surreal visual fever dream of sinuous movement, billowing fabrics (a la Loie Fuller), projected paintings, and swelling music. After recovering from a spinal injury that would have confined most people to a wheelchair, Fleming developed her distinctive style of movement which reminded me of circus contortionists but less extreme. Throughout the piece, Fleming embodies O’Keeffe’s art and life, becoming a blossoming poppy, a city slicker on a skyscraper, a selkie (re)born into the sea. It was, in a word, breathtaking.

Fleming discussed her interest in O’Keeffe during a recent interview:

I connect with O’Keeffe’s work on many levels. Of course, I am especially drawn to her many paintings of flowers that allow the viewer, through form, scale, and color, to experience a transformation of reality in the experience of seeing, really seeing a flower. However, I also am moved by her personal struggles and artistic journey and her ability to draw strength through her art. There is a Celtic story of the Selkie where a seal transforms into a woman and is captured by a fisherman who hides her skin and marries her. However, after many years, she finds her skin and returns to the sea. I feel this is a story that relates to O’Keeffe’s journey as a woman and artist. In her life, she was able to reclaim her artistic skin through a bold move to the southwest after experiencing mental turmoil through her relationship with Alfred Stieglitz. Yet she remained committed to him until his death.

The work left me stunned. For those mystical ninety minutes, Fleming not only looked like O’Keeffe’s paintings - she became O’Keeffe herself. Her beauty and strength and struggle. The triumph of returning to ourselves over and over and over again throughout the course of a lifetime, especially as an artist. We sift through our experiences, our environments, our souls, looking for inspiration like panning for gold - trusting that, even during dry spells, we will strike upon it again eventually, that we haven’t found all of the treasure yet.

Maintaining a creative practice requires constant exploration of both familiar and unfamiliar ground. Recently, I’ve been pondering the Gesture Drawing series and how to bring them further into the realm of color. I adore charcoal and colored pencils but miss the vibrancy I can achieve with paint. Right now the backgrounds are blank and the only color is the bracelets. I like a simple background, even in my paintings. I like how it implies a sense of space. A sense of being noplace and anyplace at the same time. In many ways, a blank space is the most abstract form of all, defined only by its relation to the areas where there is something.

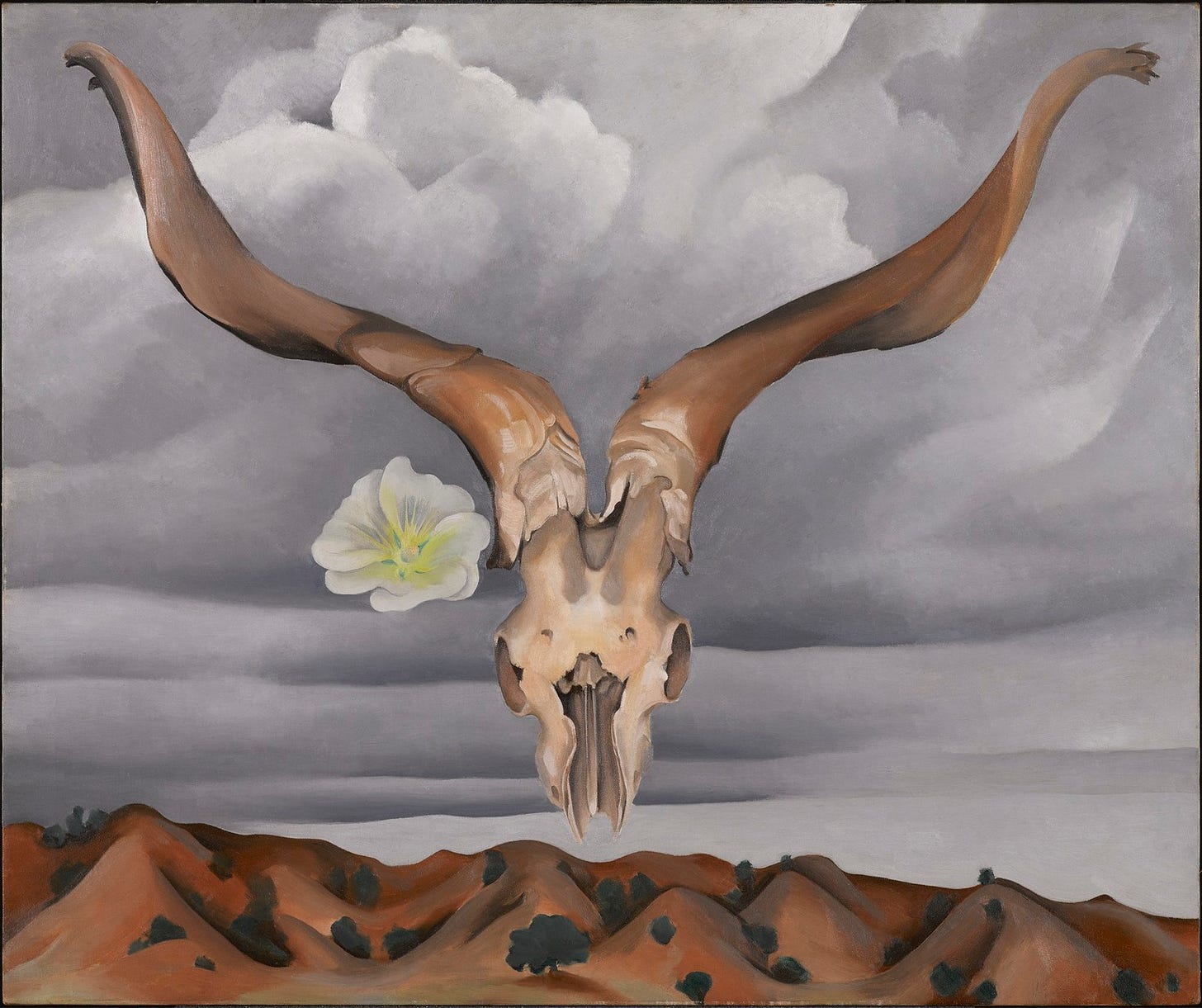

How would it change these drawings if the background was, instead, swelling multi-colored waves? Or unfurling petals? Or the otherworldly fossae of bones? What if I took a page from O’Keeffe’s book and allowed the hands to hover over a landscape, like the skull in Ram's Head, White Hollyhock-Hills?

I have a new order of art supplies arriving this week, which means it’s time for new experiments. Stick around to see where that leads and for next week’s newsletter exploring monstrosity and queerness (specifically, the chimera).

XOXO,

Sam